Fragments from the History of Classical Studies in Brno

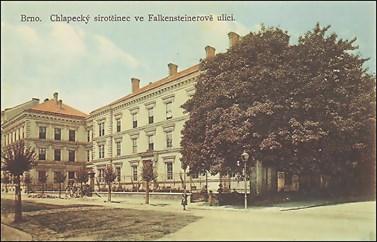

Nowadays, we can only hardly imagine the modest beginnings of Classical Philology in Brno. In the first years of the Seminar for Classical Philology, the whole curriculum was taught only by two to three people. The first, initially the only, scholar working at the Seminar was František Novotný, a recently appointed professor at the time, who was followed very soon by professors Karel Svoboda and Václav Petr. The proper teaching started in the winter semester of 1920 in the premises of a former municipal orphanage in the Gorkého Street No. 14 (Falkensteiner's Street then, todays building A).

The brand new Masaryk University tempted promising young scholars – just think of the professors Novotný and Svoboda who, at the time of their beginnings at the university, were less than 40 years old! It was their initiative that made other experts come to the university, whether we speak of the young scholars from Prague or the new graduates from Brno. The most significant figures working at the university were Vladimír Groh, a professor of Ancient History, Gabriel Hejzlar, a classical archaeologist, and especially the even younger professors of Classical Philology Ferdinand Stiebitz and Jaroslav Ludvíkovský. This new generation brought with it new approaches and study fields, as well as negotiated the first contacts with the classical philologists all over Europe and established university's involvement in the social and cultural events of the city.

There is no doubt that the foundation of a brand new university could not do without many problems. The university lacked rooms for offices and classrooms, as well as the necessary administrative staff. Nevertheless, the correspondence of the founding professor František Novotný provides us with rare examples of a successful tilting at windmills. The professional enthusiasm of prof. Novotný is also apparent from a request he made in the July of 1922, asking for the purchase of a chair-bed “so that the director (of the Seminar for Classical Philology) may pass the night at the university, until he is able to permanently live in the city, without any costs and with no further inconveniences”. Unfortunately, the documents are silent about whether the request was accepted or not.

František Novotný (1881–1964)

František Novotný can doubtlessly be regarded as a founder of Classical Philology in Brno; however, he was also active outside his department. In 1930, he became a dean of the Faculty of Arts, whereas after the re-opening of Czech universities after the WWII in the summer of 1945 he was appointed pro-rector of the Masaryk University. He was a member of the Czech Academy of Sciences and he also worked for the Polish Academy of Sciences in Krakow. Nevertheless, he became famous especially as an editor and publisher of Plato's works. He spent half of his life in Brno researching, translating, and teaching. Although he was popular among his students, he was also much feared due to his renowned strictness. He taught all linguistic disciplines; students today know him especially as an author of the handbooks of Latin grammar and its development and a co-author of the most extensive Latin-Czech dictionary.

Karel Svoboda (1888–1960)

Karel Svoboda was employed by the university in 1920 and stayed in Brno until 1935, when he moved to Prague. He taught his students the History of Greek and Latin literature, ancient philosophy, as well as fine arts. However, his focus was on the aesthetic values of literary works, history of Classical Philology, and the ancient tradition in the European and Czech cultural contexts. His interest in the philosophy of Ancient Greece led to the publication of the monograph Zlomky předsókratovských myslitelů (The Fragments of pre-Socratic thinkers, published in 1944).

Shortly before the beginning of the war the professor staff of the Department of Classical Philology was reinforced by Jaroslav Ludvíkovský, who, after the formation of a fascist Slovak State, was expelled from the university of Bratislava, where he had worked since its founding. He was appointed the head of the department right after his arrival to Brno but he did not get to teaching, as on November 17th 1939 all Czech universities were closed.

Masaryk University suffered numerous losses during the six years of war. A part of its buildings was given to the German Technology Institute, other parts were distributed between German offices and army. Many of the buildings were also damaged during bombings. Most of the funds of the university libraries were plundered. However, the most painful losses were on lives – 45 teachers did not survive the war, including Vladimír Groh, a professor of ancient history and a member of the Sokol resistance, who was shot in September 1941 in the yard of Kounic student dormitories.

Vladimír Groh (1895–1941)

Classical philologist Vladimír Groh started to teach students of Masaryk University Greek and Roman history in 1931. He was well known for his precise work with sources (he translated Livius) as well as for his applying the knowledge from different disciplines in his work (e.g. archaeology, papyrology, geology, climatology, etc.). In 1936, he was appointed the dean of the Faculty of Arts; during the war he joined the Czech resistance network. In February 1941, he was arrested and in September of the same year executed for the preparation of high treason. Nowadays, the street adjacent to the area of his home faculty bears his name.

Post-war enthusiasm was manifesting itself considerably during the works on the reopening of the university and its return to the pre-war condition. Many of the students were spontaneously helping with cleaning the buildings after their occupation by Nazis, whereas the association of university officials and pedagogues was restored almost immediately.

Freedom of the Czechoslovak universities was violated again with the rise of the Communist Party to power in February 1948. This was demonstrated both in personal and financial spheres – politically unacceptable teachers were warned to adapt to the new worldview, they were deprived of all important positions, and watched diligently. Among classical philologists, this applied to professors Novotný and Ludvíkovský whose cadre reviews were stained by the case of a historian Bohdan Chudoba – both professors stood up for this anticommunist rebel, when his habilitation was being obstructed by the committee.

"Secretary of the department reviewed the current activity of prof. Novotný, especially in political terms. (…) Comrade prof. Novotný explained his opinions: when recruitment to ROH [Revolutionary Trade Union Movement] was taking place, he was told that everyone had to join. However, Prof. Novotný then asked KOR [Regional Trade Union Council] and found out that the membership was voluntary. His refusal to join was to serve as a proof that membership indeed was voluntary. (…) Concerning the refusal to sign the declaration about atomic bomb, he said that he had a very refined sense for style and did not want to sign a declaration clearly composed in a hurry and, thus, unacceptable for his sense of style." (from the report about the function of the department, 1951)

A short period right after the war was overflowing with numbers of students interested in studying at the restored universities. This high demand was one of the reasons for establishing the admission exams. The second reason was the so-called “assessment of national and political reliability of the university students”. Besides students' knowledge, a cadre review was equally important for his/her acceptance or rejection.

Ferdinand Stiebitz (1894–1961)

Ferdinand Stiebitz is famous primarily for his numerous translations. He is said to have acquired the first salary for translating Latin as soon as he was 18 years old, which he used to buy a bicycle. Even today, the readers of ancient tragedies and comedies are familiar with him, as he translated these with unusual taste for spoken language and Greek dialects – e. g. he used various dialects of Czech as well as Slovak language. With his charisma and sense of humour he managed to win over both his students and the general public. Nowadays, students still use his textbook on the history of Greek and Roman literature (Stručné dějiny řecké a římské literatury).

Jaroslav Ludvíkovský (1895–1984)

Professor Ludvíkovský worked in Bratislava, where he was dealing with Greek novels and the concept of humanity as it was viewed by the ancients. He arrived at the University of Brno in 1939, forced by the change of political conditions in Slovakia. Most of his research was dedicated to medieval Czech literature and together with the classical philologist Bohumil Ryba from Prague, he can be considered a founder of Czech Medieval studies. He is especially known as an editor and a translator of the so-called Legend of Kristian.

During the 60s there was a huge increase of those interested in studying at the University (which was for political reasons renamed to The University of J. M. Purkyně). This was apparent at the Department of Ancient History, too. At the Department, this decade is marked by passing the torch to the younger generation. The politically looser, more favourable atmosphere at the end of the 60s brought forward a quick academic progress, which resulted in the young associate professors Češka, Bartoněk and Hošek becoming the professors. The presence of the historically first female members of the academic staff was understood as a ground-breaking change – these were a postgraduate Jana Nechutová and a research assistant Daša Bartoňková.

Reconsolidation after August 21st 1968 had a huge impact on the University. Just like in the spring of 1948, cadre reviews of students and teachers were made. Nevertheless, the Faculty of Arts was affected the least of all and the classical philologists in Brno were fortunate enough to be spared from these practices. Josef Češka was appointed the head of the Department, and he tried, according to the motto “well… better not cruising for a bruising”, to avoid any problems beforehand, which he sometimes did more carefully than necessary.

During the next twenty years, the academic life at the university appeared to be “frozen in time”, an academic promotion was practically impossible and the Faculty of Arts became the Faculty of postgraduates.

Not even the uneasy atmosphere could have stopped the diverse and vigorous activities at the Department.

Latin students even organized the evenings of poetry or performed plays with ancient motives. A society for the supporters of the living Latin was created by Jan Šprincl. He was an extraordinary figure also when it comes to translating. Unlike his colleagues, he was translating from Czech to Latin and Greek, not recoiling even from the works of Otokar Březina.

Josef Češka (1923–2015)

Josef Češka dedicated almost all his life to this university. At the beginning of the 70s he was appointed the head of the Department of Ancient Culture, while he also worked as a vice-dean several times. He primarily taught the ancient history, whereas in his research he focused on the late antiquity (his honourable successor in this field became Jarmila Bednaříková). In one of his publications, he analysed the relationship between Christianity and Roman Senate, to the students, he is well-known for his translation of Ammianus Marcellinus.

Antonín Bartoněk (1926–2016)

Many students vividly remember Professor Bartoněk because, despite his advanced age, he was still teaching at the Department of Classical Studies almost to the very last moment (from 1952 without any breaks). He taught the students of Ancient Greek and Latin, while scientifically, he was interested in the Greek dialects, especially the Mycenaean. In 1958, he provided the Classical Philology in Brno with a worldwide fame, when he published his renowned paper helping to decipher Linear B script. His friendship with a prominent British mycaeanologist prof. John Chadwick is notorious.

Although the events of November 1989 went forward with some delay in Brno, the Faculty of Arts certainly did not fall behind the revolutionary course of events. On November the 20th, a huge assembly was gathered at the forecourt of the faculty in Arne Nováka Street. A linguist Dušan Šlosar became the most active member of academic staff in these efforts. There were several students leaders, too, including Roman Švanda, a student of Czech and Latin languages today known as a committed poet and a cafeteria owner. As for the academic staff of the Ancient History Institute, there were no revolutionary activist except for Zdeněk Zlatuška who took part in the copying of samizdat texts and, together with his wife, was in close contact with the dissidents in Prague.

At the beginning of 1990s, many scholars finally got the opportunity to finish their degrees, which were before unattainable to them because of their “inappropriate” political standing during the Communist era. Thus, the faculty administered by research assistants gradually became a place where higher degrees took the lead. The injustices suffered by many excellent scientists were, at least retroactively, compensated by granting honorary degrees. These ceremonies could not do without Latin speeches performed with splendour and elegance by prof. Bartoněk, the university's promotor.

In 1992, prof. Jana Nechutová became the first female head of the department. Moreover, in 1995, she became the first, and up to now the only, female dean of the Faculty of Arts. However, it has to be mentioned that she followed in this function four distinguished men - František Novotný, Karel Svoboda, Vladimír Groh, and Ferdinand Stiebitz. In 1998, another woman, Daša Bartoňková, took the reins as the head of the department.

In 1993, the Department of Classical Studies came with a new study programme of Modern Greek. A key figure from its very beginnings of the programme has been Růžena Dostálová, a distinguished scholar and translator in the field of Byzantine Studies. Under the leadership of prof. Nechutová, the department's research got more involved in the editorial work with the Latin works produced in Czech lands. Already in the 1940s, prof. Ludvíkovský started to deal with Medieval Studies at the department; however, the isolation of the Eastern Bloc impeded the full development of the research.

Right after the start of a new millenium, the department extended its offer study programmes by including new fields of study. The Mediterranean Studies became the first of these brand new fields and it has provided students with a broader insight into the development of the Mediterranean cultural space from the antiquity up to nowadays. The students of Mediterranean Studies do not become familiar only with the classical languages and literatures, but also with Romance languages, Modern Greek, and also Arabic, including the national literatures and recent political situation of the particular regions. Moreover, Ancient History can now finally be studied as an independent study programme, which is also thanks to its long tradition reaching as far as to the First Republic.

Due to the extensive reconstruction of the former orphanage building of the Faculty of Arts, the Department of Classical Studies was compelled to move into the former buildings of the Faculty of Medicine in Komenského náměstí (building M). This included also the moving of the plaster copies of famous ancient statues which were obtained by the department from the collections of the cancelled German technical school. However, these did not return to the department's precincts after the reconstruction but were installed in the interior of the reconstructed buildings A and B to be admired by all.

Jana Nechutová (born 1936)

Professor Nechutová studied at the Faculty of Arts, Masaryk University, Brno, and, from 1961, she was working at the department as a postgraduate student. Together with Daša Bartoňková, she was one of the first women belonging to the academic staff of the contemporary department (The Ancient Culture Institute). She also became the first female head of the department and even a dean of the Faculty of Arts. She is a significant representative of Latin Medieval Studies in Czech Republic. For many, she has been inherently tied to the research on Czech Reformation and its main figure John Hus. Students are also well acquainted with her handbook on Czech-Latin medieval literature.